The recent news that Joe Satriani is set to release music from his San Francisco new-wave-ish band, The Squares, brought on a bit ‘o’ nostalgia.

But first things first: Squares: Best of the Early 80’s Demos is due to drop April 5, on Satriani’s Strange Beautiful Music label. John Cuniberti, who was The Squares’ live and studio engineer—and, after Satriani started his solo career, the co-producer of the guitarist’s groundbreaking, platinum-selling, Grammy-winning Surfing With the Alien (1987)—kept all of the band’s recordings and had the foresight to preserve and digitize the tracks, making this peek into Satriani’s musical past possible. Apparently, it was only after looking back over his career through his son ZZ’s Supernova documentary that Satriani became comfortable with going public about The Squares music.

“I didn’t want to hold anything back anymore,” he told Gary Graff of Billboard.com. “The [Squares’] music was actually really good and we were really something unique, in retrospect. Back then we thought we were failing, but now I realize there was nobody quite like us.”

I can second that. In San Francisco, at that time, there was no band like The Squares. And I didn’t know what to make of them.

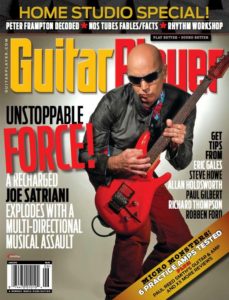

The Squares, left to right: Satch, bassist Andy Milton, drummer Jeff Campitelli [Photo courtesy Mad Ink PR]

On one level, The Squares played the same crap and sorta-nice San Francisco Bay Area venues that the rest of us did. Maybe they played a bit more often, and maybe they headlined a bit more, and maybe they got to play the nicer clubs more regularly than some of us, but The Squares were still a part of the surging mass of musicians looking to break out of the local scene. They weren’t apart from everyone else—they were simply gears in the larger S.F. scene.

Somehow, my manager at the time had a cassette demo by them, and when he played it for me, I just shrugged. Of course, I did that to every band that threatened my ego and that might stand in the way of my own band’s ascent. I can hear myself saying, “Yeah. Don’t dig the singing. Songs okay. Production basic. And what’s up with that guitar player?”

Oh, what an arrogant douche I was. But I was also committed to a very narrow stylistic quest along with a lot of bands in my little musical community—the evolution of punk’s bombastic inspiration into more commercial new wave music. To many of us in that crowd, flying the flag meant translating the energy of punk into perhaps more pop-dressed melodicism, but still keeping songs short and guitar solos brief or non-existent.

Satriani shattered that notion, and it was thrilling, challenging, and, well, weird.

This was before hair metal exploded—although we all should have seen the world changing when Van Halen’s debut album was released in 1978—so the stuff Satriani was tossing into The Squares’ songs was somewhat frightening to a confused punk rocker/Beatles devotee such as myself.

I mean, get a load of what he does in the pre-release single of the new album, a cover of “I Love How You Love Me.” (And listen as if it were 1980.)

Eventually, I had to see the band live, because we always checked out the hot acts, and so many people were raving about The Squares that I was starting to go crazy envious over all of the hype about them. (I don’t believe my band ever opened for them—the fog of memory being what it is—so I think I probably crashed one of their shows at the Keystone Berkeley or some other joint.)

And, yeah, I was brought to my knees.

Here’s how my brain likely assimilated what I was confronted with that night:

[1] Ego Check #1: I write songs as good as that, so “pootey pootey pootey.”

[2] Ego Check #2: I jump around onstage more, and audiences like to see stuff like that, so “pootey pootey pootey.”

[3] No-Escape Realization #1: I will never ever be able to play guitar with such creativity and brilliance as this dude. He has murdered me. And all of my guitars, too.

[4] No-Escape Realization #2: The culture’s outlook on guitar playing is rapidly changing into a far more accomplished and technical landscape than three barre chords and a cloud of dust. I had better get my house in order and join this new movement.

[5] No-Escape Realization #3: I still won’t ever be able to play like that. I am f**ked. (Sniff. Sigh. Distress.)

But although fame and fortune didn’t come to The Squares—and, down in the throes of my asshole self back then, I probably threw myself a little self-absorbed party of relief over their lack of success—that little San Francisco band DID point to the future.

Satriani proved that immense technique could serve pop music without patronizing either discipline. He also showed the way to hybridization—that myriad musical influences could co-exist in a bountiful stew and lead fans out of conventional listening experiences. Furthermore, like some kind of guru, he illustrated by example that making transcendent and thought-provoking music is difficult, and that musicians of all types shouldn’t give up or get lazy before expending every last bit of sweat to ensure the music you make is the absolute best that you can make it. In short, there’s no coasting—no “it’s good enough”—in this endeavor.

I learned those lessons that night, and I’ve seen the man himself continue them decades later, when I’ve watched him in his cozy home studio work to get a melody just right. Even counterpoint parts that will be dropped down in the mix get his full attention as if they were featured melody lines. His work ethic is unbelievable—it’s the process of a master creator.

A few years after I saw The Squares, Satriani released Surfing With the Alien, and we all know what that album did for him, for guitar, and for music in general. It was an epic moment, and one that continues to inspire guitarists to this day.

Obviously, I couldn’t come even galaxies close to Satch as a player. But I did absorb his lessons that night so long ago.

They informed my approach to music, and made me more serious and tougher on myself, as well as someone who tried to toss convention aside and look for new horizons. While that discipline didn’t help me create music the world wanted to hear, it did guide my journalistic excursions—forging a personal code that always made me strive to be a better editor as I managed Guitar Player magazine for more than 20 years.

And much of that is thanks to Joe Satriani and a band that made me crazy jealous.

Great historical take, Michael! I felt the same way as I saw some local bands around me play amazing! The Raisins, The Bears, psychodots…