Your Guitar-Star Influences Are Great, But What About the Help of Unsung Buddies?

I’ve had the great privilege of interviewing hundreds of successful guitarists. One of the subjects I often like to explore is how a player’s talent evolved from “open to all input” to laser focused on the elements that made them a bona fide guitar hero. An important aspect of that line of questioning has to with identifying musicians who influenced them, and the answers are usually names such as B.B., Freddie, or Albert King; Duane Eddy; Maybelle Carter; Steve Cropper; the Beatles; and so on. Sometimes, such in the case of Brian Setzer, a significant guitar teacher is mentioned. Or perhaps a player credits one or both of their parents with support, guidance, or actual lessons.

But I don’t believe I’ve ever asked a musician about the friends in his or her life who may have fired them up and got them in the game. Perhaps that has been a long-standing misfire in my journalism career. I mean, sure, a story about being awestruck by Jeff Beck or Jimi Hendrix is likely more interesting to readers than the tale of some kid down the block who cajoled a player into their first garage band. However, those everyday people—playmates, classmates, bandmates—are critical influencers and should also be considered essential components of one’s musical evolution.

I think it would be groovy to fix this omission and salute those unsung yet important friends in our creative lives. I’ll even start it off.

I’m obviously not a rock star or any kind of a guitar hero, but even so, I do have a couple of people who made it possible for me to follow my path through crap bands and good ones, getting a few record deals, owning recording studios, and ultimately getting the Editor in Chief positions at Electronic Musician and Guitar Player. In fact, if it weren’t for these personal motivators, I very much believe I may have ended up working at my dad’s coin-metered laundry company or stayed in the newspaper game.

You see, to my middle-class Italian family—where I was raised by parents and grandparents and aunts and uncles who survived the Great Depression and World War II—a career in music was considered frivolous. I was supported to a point, but any serious talk of committing my life to the service of music was met with derision and, at times, outright anger. Small wonder that I didn’t begin playing the guitar seriously until I was in high school, and I didn’t join my first band until college.

If it weren’t for the godsends below, I shudder to think how my life would have turned out. All the joy and beauty of making music—as well as the invulnerable oasis of safety and solace it brought me in times of darkness—would likely have been delegated to the pile of my broken dreams. Below are four of my heroes…

If you’d like to salute yours, send me a bit about yourself, a paragraph or two as to why your unsung friend was instrumental to your growth as a musician, and, if possible, a photo of that person. Send your submissions to me at mike@guardiansofguitar.com, and I will add YOUR heroes to this story…

Kirk Griffin

Kirk was the first person my age who I actually saw leading a band—a ‘50s cover act called Greased Lightning that performed at my high school. I was insanely jealous. By the time I was in college, Kirk had formed a group called Whitewater that played the hits of the ‘50s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. I told him I was playing guitar, and he said the words that changed my life: “Cool. Do you want to play in my band?” No way was I good enough, but Kirk was patient, and he covered all the tough stuff anyway. I learned tons about band leadership, stagecraft, arranging set lists, and musical discipline from him.

Then, I screwed him over.

I was experimenting with original material by then, and the other band members in Whitewater wanted to jam on my songs. Kirk has not invited for reasons I can’t even remember today. Within a month, Kirk fired us all, and his band became my band. Almost immediately, Kirk transformed himself into one of the first Elvis impersonators in the USA, and his “Jesse King as Elvis” show was a smash hit.

Thankfully, Kirk and I stayed friends—not as close as before my unwitting treachery, but good enough to check in with each other from time to time, and he even helped build my first recording studio (more on that below). I kept writing songs and playing in bands, and that would have never happened if Kirk had not shown me what my heart and soul were aching to do. He had also accepted me as a professional musician, and that meant everything to me.

Sadly, Kirk did not fare well later in life. He developed health problems, marriage problems, and financial problems, and he passed away at just 54 years old in 2010. I still miss his goofy laugh, as well as his absurdly mega-optimistic outlook on life. He always thought anyone could do anything, even when they couldn’t. I loved that kind of crazy.

Stephen M.H. Braitman

[Silhouette, 1979, left to right: Leasa Wilson, Deano Valentini, Stephen M.H. Braitman, me]

I met Stephen when he was the editor of City Arts magazine, and I was out begging for freelance writing jobs. Somehow, he got involved with my band Silhouette, and he became my first manager.

Stephen was also the first record collector I had come across, and every wall in his apartment was covered with ceiling-high shelves filled with vinyl album and singles—all precisely categorized and alphabetized. He knew about tons of obscure punk and rock bands, and he endeavored to kick me out of my pop-rock comfort zone by filling my head with all kinds of different music. He was one of the smartest people I had ever hung out with, and he patiently guided me out of my artistic naiveté, inspiring me to dig deeper and seek my own sound. He was an enthusiastic cheerleader, as well. He used to stand by the mixing desk with a cassette deck when we played, and those gig tapes often captured him madly clapping along with the band. Stephen’s support and guidance made it possible for me to develop the work that made my bones—one of San Francisco’s first multimedia rock shows, Streetbeat. Stephen helped fashion my libretto, songs, and mad dream into something bigger by introducing me to a director and a choreographer. I still can hardly believe it all happened, and it might not have, if not for Stephen’s unwavering belief that I could do it.

Neal Breitbarth

[Neal Breitbarth (far left) with his Crumar synthesizer.]

Neal and I went to the same high school, but he was a year behind me, and I might not have hung out with him if Kirk Griffin hadn’t introduced us. (Kirk again!) That was a life-changing introduction. Neal was not only the best piano player I ever heard, he was also one of those guys who could build an entire house out of a wooden matchstick, and then do all the electrical and plumbing, too. We did some songwriting together, and eventually ended up in a later version of Silhouette. Then came Streetbeat, and Neal not only composed and performed a beautiful prologue on grand piano, he acted as musical director, helped arrange the songs, built a few sets, recorded the sound design elements, and pitched in whenever anything lurched to a temporary halt. When Streetbeat went into turnaround (ultimately dying in some sort of theatrical-financing hell) we started looking for another big project, and Neal’s family put up the money for us to open our own recording and video studio, Sound & Vision. The studio started in an empty warehouse, and Neal designed and built Sound & Vision from nothing. That studio lasted more than ten years, and our clients included local bands, producer Matt Wallace, NASA, Pablo Cruise’s Cory Lerios (who was working on the music for Max Headroom and won the award for loudest monitoring levels of all time), and even Roto Rooter (we recorded one of their jingles). At Sound & Vision, I was immersed in a magnificent laboratory for learning audio engineering, record production, and video editing, and I wrote tons of songs and made lots of recordings in that joint. The studio added immeasurably to my skill set, reputation, and industry profile, and none of this would have happened without Neal as the driving force.

Marina Hotchkiss

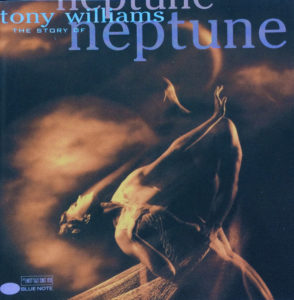

[Marina Hotchkiss modeling on the cover of Tony Williams’ The Story of Neptune, 1992]

My first wife was a brilliant and stunning ballet dancer, and she was raised in a family of artists where artistic expression was celebrated—an alien concept compared to how I was brought up. She knew so much about theater, film, photography, painting, choreography, and enigmatic musicians that I usually felt provincial and unworldly in her presence. But she did for me what my family was incapable of doing. She completely accepted me as an artist—albeit of the “pop” variety—and encouraged me to see myself as a creator, to trust my instincts, and to believe in myself as an artistic being. She also constantly blew my mind by introducing me to art that was not in my creatively claustrophobic orbit. If not for Marina, I wouldn’t have absorbed artists and art forms that still drive my inspiration today, such as Jean Cocteau, the Ballet Russe, German Expressionism, Michael Powell, and Surrealism. She was the first person to truly shatter all of my fears and self-doubts—everything I had collected through years of a conventional middle-class upbringing and parents culturally incapable of viewing art as a viable life’s work. To Marina, I was a part of the artistic community. Period. She never said stuff like that, but our house was full of creative ideas, grand projects, enthusiasm, debate, and support. I had lead bands and written lots of music—as well as composing Streetbeat—before I met her, but Marina was the final glorious step to freeing me of my past baggage and paranoia, and accepting my lot as a creative whacko. She was also the person who showed me a want ad in the newspaper about a music magazine looking for an assistant editor. That magazine was Electronic Musician, and that job changed my life’s path immeasurably. No EM, no Guitar Player. No GP, no career as a guitar journalist and all the benefits that life brought to me—including to this very moment and Guardians of Guitar.